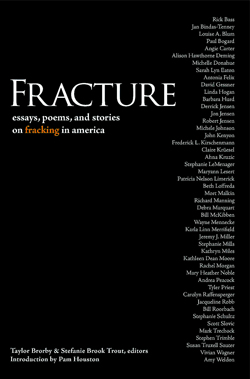

Fracture: Essays, Poems, and Stories on Fracking in America

Fracture: Essays, Poems, and Stories on Fracking in America.

Edited by Taylor Brorby and Stefanie Brook Trout. Ice Cube Press, 2016

Paperback, List Price: $24.95

Reviewed by: Claire Kortyna

In Fracture: Essays, Poems, and Stories on Fracking in America, editors Taylor Brorby and Stefanie Brook Trout bring together more than fifty writers to create an arresting collection of poetry and prose about one of the great environmental issues of our time: fracking. In the voices of these poets, journalists, and storytellers Fracture rants, raves, laments, and laughs with blackened bitterness. While all of these pieces are united in their anti-fracking stance, each piece provides a unique perspective on this complicated issue. Poised against the chasm of ignorance and misleading propaganda that surrounds fracking in America, these essays give voice to the people and the land that this industry seeks to silence. As Rick Bass writes in his essay, “The World Below,” “The earth is mysterious, the earth is alive – even as we war against it” (p. 175). This insight, among many others, opens readers’ eyes and attempts to foster an ethical, informed discussion about the disaster that continued fracking will inflict on our homeland.

These creative voices weave together an artful tapestry of protest and awareness through their strong lyrical prose, well-developed characters, and the stark honesty of first-hand experiences. With landscapes and settings ranging from North Dakota to Texas, this issue transcends regionalism and local geography to become a national concern. Together, these artists express an unwavering conviction that the economic benefits that fracking provides will never justify its environmental costs.

In “The View from 31,000 Feet: A Philosopher Looks at Fracking,” Kathleen Dean Moore takes several flights, and observes the new landscape fracking has wrought. Moore grapples with the emotional impact of this changed view and writes:

Let me try this: You’ve seen military cemeteries near battlefields, with closely ranked rows of crosses as far as you can see in any direction, yes? And you think my God, how is this possible, that humans could do this to one another? Now imagine that you’re in that cemetery, and it’s night, and all those crosses suddenly burst into flame – flames, flaring the methane from drilling rigs, closely ranked rows of flames as far as you can see in every direction. You think, my god, how is this possible, that humans could do this to the Earth? (p. 83)

Moore’s analogy reminds readers of an often-ignored truth: the destruction of our landscape spells our own. Our lives are not separate from the life of the land whose bounty we thoughtlessly plunder, always seeking the quickest fix. The essays and poems in Fracture are eyewitness accounts, testaments, and well-written engaging stories. The writing is stark; it resonates. Respect and love of one’s place flow underneath the collection’s hard-hitting accounts of ruined prairies and poisoned gulfs.

To read this book demands patience and time. Each piece requires savored consideration and weighted digestion. Fracture cannot, and most likely should not, be devoured. It cannot be consumed in long, sustained sittings. Instead, it should be picked up, read, and placed down, again and again, time after time. Each new piece stacks upon the others like bricks of revelation that sit heavily with the reader, percolating long after they finish the book. Claire Krüesel, in her poem “Surfacing,” writes, “The North Dakota Indian Reservations / no longer reserve much, decorous / as charred lace. / The Bakken’s fiery tongues / punctuate uncertain fields, hungry now” (p. 161). In such a substantial collection, where many essays include hefty amounts of startling research, statistics, and information, poems like Krüesel’s come as a breath of fresh air – a more imagistic rumination on the realities of this environmental blight.

Fracture emerges in the tradition of other environmentally focused collections such as Terry Tempest Williams and Stephen Trimble’s Testimony and Rick Bass and David James Duncan’s The Heart of the Monster. In a sea of pro-fracking politicization, Fracture seeks to show readers that there is another facet to this seemingly one-sided discussion. It serves as a sounding alarm for the mute landscape fracking abuses and calls for a more responsible re-imagining of energy resources.

Overall, this collection fulfills an important role: it provides an essential perspective in the heated conversation about our nation’s resources in a way that fosters environmentally ethical discussion. It covers a remarkable range of material in a variety of narrative forms, and each of these renderings, for the most part, provide their own unique insights. The sheer volume of contributors however, while evidence the incredible importance of this topic, makes the collection feel dauntingly dense at times. And for those whose beloved landscapes are not echoed in these essays, maintaining an established emotional investment may be a struggle. But the essential message of this impressive book remains universal: people care about their environment – the one that fracking is harming – and it’s time for America to pay attention.